History of Temperature and Rainfall Measurement in Kathmandu

Nepal’s climatological record officially begins in 1879, when the British established a weather station at the Legation Hospital Compound in Kathmandu, an initiative documented by Nayava (1982)[i]. Temperature and rainfall were recorded, although intermittently, until the mid-1940s. Yet, archival traces of early colonial writings on Nepal suggest that meteorological interest in Nepal predates this by many years: temperature was reportedly measured in Kathmandu as early as 1793, several years before the British Residency was officially established. Notably, it positions Kathmandu ahead of India under East India Company rule in terms of meteorological measurement.

This essay, which is Ajaya Dixit’s quest for History-1, discusses early writings on meteorology and data in Kathmandu.

Context

Nepal’s climatological record officially begins in 1879, when the British established a weather station at the Legation Hospital Compound in Kathmandu, an initiative documented by Nayava (1982)[i]. Temperature and rainfall were recorded, although intermittently, until the mid-1940s. Yet, archival traces of early colonial writings on Nepal suggest that meteorological interest in Nepal predates this by many years: temperature was reportedly measured in Kathmandu as early as 1793, several years before the British Residency was officially established. Notably, it positions Kathmandu ahead of India under East India Company rule in terms of meteorological measurement.

Meteorology, the study of atmospheric phenomena, has its origins in ancient societies, which observed weather to manage crops, predict seasonal changes, and interpret natural events. In Magadh, where Chanakya composed the Arthashastra, rain gauges were installed and records were utilized to assess agricultural production for taxation purposes. Land with higher rainfal

l was expected to yield more than land with less rain, a practice that highlighted the non-uniformity of rainfall across an area. Today, this concept is understood as spatial variability. Varahamihira’s Brihatsamhita, written between 505 and 587 CE, in present-day India, details the use of wind vanes, the methods for forecasting rainfall, and locating groundwater.

In Magadh, rain gauges were installed and records were utilized to assess agricultural production for taxation purposes.

Galileo’s early thermoscope (1593) laid the groundwork for measuring temperature quantitatively. By the 16th and 17th centuries, early researchers had begun creating the first temperature measurement networks. The spread of standardized thermometers allowed for the collection of temperature data across regions, leading to weather maps and early forecasting. Other instruments, such as barometers (Torricelli in 1643), anemometers (Alberti in 1450), and rain gauges (by Prince Munjong in 1441), expanded the meteorologist’s toolkit. As technology advanced from Galileo’s glass tubes to digital and satellite sensors, temperature became a key metric supporting daily weather predictions and modern climate science.

In Britain, meteorology established itself as an institution in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, spurred by the development of precise measuring tools. Its expansion into colonies, however, was driven by imperial interests—particularly through the East India Company and later administrative agencies. Meteorology evolved into a professional discipline across the empire, transitioning from private diaries to organized scientific study. This created a vast collection of weather data, now essential for climate research—and once crucial for supporting imperial economic, military, and political objectives.

Meteorology evolved into a professional discipline across the empire, transitioning from private diaries to organized scientific study.

The development of more reliable instruments played a crucial role: in 1714, Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit introduced the first practical mercury thermometer, allowing for consistent and accurate reading, accompanied by a reliable scale. Anders Celsius’s centigrade system followed this in 1742, which soon became the standard in scientific work. That timing, for example, 1793, places Nepal roughly a century behind Britain, where systematic temperature recording began in the early 18th century.

Early Meteorological History

This section briefly overviews early colonial and other documentary references to Nepal’s climatological history.

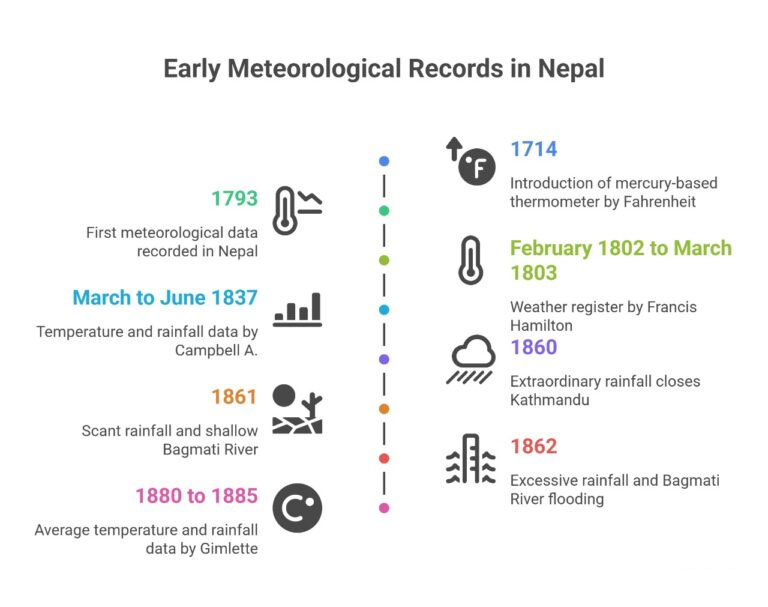

- William Kirkpatrick’s survey in 1793 included records of discrete temperature readings from Chisapani, Chitlang, Kathmandu, and the banks of the Tadi River in central Nepal. [ii]

- Francis Hamilton’s account includes a detailed weather register spanning February 1802 to March 1803. Temperature readings, recorded in Fahrenheit, were taken at four intervals—dawn, noon, three hours past noon, and nine hours past noon. The register also logs barometric pressure and wind conditions. From July 1802, rainfall measurements (in inches) were added using pluviometers, with station locations identified by latitude north. Data were collected from sites including Ghorasan, Kachruya, Bhagawanpur, Norkatiya, Dhonhara, Jukiyari, Gar Pasara, Bichhakori, Hetauda, and Kathmandu. Observations also noted haze, cloud cover, dew, and general atmospheric conditions[iii].

- Campbell A., between March and June 1837, recorded air temperature, Wet Bulb Temperature (WBT), and rainfall at the Nepal Residency. The WBT, measured using a thermometer wrapped in wet muslin cloth and exposed to airflow, reflects the lowest temperature reached through evaporation—a proxy for humidity and heat stress. Although formal adoption of WBT came later, references appear in Kathmandu’s 1838 records, suggesting early colonial experimentation. By 1844, the Army Surgeon General of the British India Government had issued procedural guidelines, marking the method’s gradual institutionalisation. The inclusion of the WBT in such early data underscores a growing colonial preoccupation with documenting environmental conditions—particularly in climatically challenging regions—even before the technique gained formal recognition[iv].

- Padma Jung Rana, son of Prime Minister Jang Bahadur Rana, recalled that from the 10th to the 12th May 1860, all courts and public offices were shut due to what he described as “something phenomenal in the history of meteorology in Nepal.” The episode points to an unusually early onset of the monsoon. The following year saw a stark reversal: rainfall was sparse, and the Bagmati River dwindled. In response, the Prime Minister, renowned for his elephant hunts, ordered a trench dug into the sandy riverbed of Bagmati to provide the animals with a “splendid swimming bath.” By 1862, the pendulum swung again. The valley received excessive rainfall, and the Bagmati burst its banks. These early observations offer anecdotal insights into the monsoon’s variability and its implications for infrastructure and ritual displays of power[v].

The episode points to an unusually early onset of the monsoon. The following year saw a stark reversal: rainfall was sparse, and the Bagmati River dwindled.

- H. Gimlette compiled monthly temperature and rainfall averages at the Legation Hospital Compound, within the premises of the British Legation, for the period 1880–1885, and reported an annual mean precipitation of 55.9 inches[vi].

Expansion of Data System

- The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) in New Delhi compiled mean monthly climatic values recorded in Kathmandu, then the site of the British Residency, covering the periods 1901–1940 and 1941–1960 (Nayava, 1982). Continuous rainfall data for Kathmandu have been available since 1921, and from the 1940s, rainfall records from the Sundarijal Reservoir and Sundarijal Power House have also been archived by the IMD in Pune.

- The IMD established 104 hydrometeorological stations across Nepal from the late 1940s to mid-1950s (Nayava, 1982). In 1961, a project was initiated to enable continuous data collection to support power generation and irrigation planning. This included establishing a groundwater section within the Department of Hydrology and Meteorology, backed by technical assistance, data collection and analysis training, and funding for equipment and operational costs.

- A nationwide network of 95 stream-gauging stations was created to monitor surface water flows. Additionally, the United Nations Special Fund financed local costs for a preliminary survey of the Karnali River[vii].

Observation and recommendation in historical documents

Observation

1986 report of the Department of Irrigation, Hydrology and Meteorology, Ministry of Water Resources, Babarmahal, Kathmandu stated:

“Very little had been done in the field of hydrology in Nepal before 1960. The Swiss mission in the country had collected flow data in Roshi Khola at Panauti. The Government of India had collected flow data at the proposed site of the Trishuli Hydropower project in the Trishuli River and at three sites in the Koshi River basin for the Koshi barrage project. In 1961, under a special UN fund program, the collection of hydrological data was started in the Karnali river basin for carrying out a feasibility study of a power project in this basin.”

The report also said, “A joint hydrological investigation project between HMG\Nepal and USAID\Mission to Nepal began in 1961. The project was undertaken to establish a nationwide hydrological data collection system with a centralized agency to collect, compile, and publish data produced by the network. The project was implemented in May 1962 by the Hydrological Survey Section under the Department of Electricity. The Section was then transferred under the Department of Irrigation and Water Supply, and in 1965, it was expanded into a Hydrological Survey Department. The department’s name was changed to the Department of Irrigation, Hydrology, and Meteorology in 1966. The hydrology division functioned as a section under the department within the Ministry of Food, Agriculture, and Irrigation from 1972 to 1979. As a result of the reorganization of the ministries in 1979 and the formation of the Ministry of Water Resources, the Department of Irrigation, Hydrology, and Meteorology was transferred under the new ministry.”

Recommendations

Another report from 1961 by experts Veatch and Hulsing, commissioned to recommend a system for systematic monitoring of hydrological data, highlights challenges in operating the hydrological network system. They “recommended establishing, within the Government of Nepal, a separate bureau or agency devoted solely to the collection, analysis, and publishing of hydrological and meteorological data. The report further recommended that the agency should not be under a construction agency or water development bodies, particularly not to one whose responsibility is limited to the development of only one phase of water use.”

The report “stressed the importance of (i) having a basic data collection programme aimed at multi-purpose development of the nation’s water resources and (ii) having it administered by a non-construction agency, which should be responsible for obtaining information in the areas of surface and ground water, quality of water, and meteorology. All the hydrological undertakings must be multi-purpose in scope and viewpoint; the report further recommended[viii].

All the hydrological undertakings must be multi-purpose in scope and viewpoint

Collating early data, such as records from 1886 to the present, and supplementing them with reconstructed observations from local sources, could yield valuable insights into the historical climate trends of the Kathmandu Valley. It is necessary to locate other dots: archives, reports, and the lived experience of the functionaries, of the hydro-meteorology and related agencies, to weave a comprehensive institutional history of hydrometeorology of Nepal.

[i] Janaka Lal Nayava (1982). Climates of Nepal and Their Implications for Agricultural Development Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Australian National University, February

[ii] See William Kirkpatrick An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal.

[iii] Francis Hamilton (Buchanan). 1819: An Account of the Kingdom of Nepal. And of the Territories annexed to this Dominion by the house of Gorkha.

[iv] Nepal Meteorological Register 1837.

[v] Padma Jung Rana 1909 (reprinted 1974). Life of Jung Bahadur of Nepal. Printed at The Allahabad Press.

[vi] H. Gimlette (1886) Report of the Cholera Epidemic of 1885 in Nepal; The British Medical Journal, May 22, 1988

[vii] See Skerry, C. A., Moran, K., and Calavan, K. M., 1991: Four Decades of Development: The History of U.S. Assistance to Nepal (1951-1991), United States Agency for International Development

[viii] See Water Nepal 1986, “What did experts say 25 years ago”