Rediscovering Floods

In recent decades, South Asia has witnessed increasingly frequent episodes of heavy rainfall, leading to recurrent floods in several major Indian cities, including Chennai. The city experienced major floods in 2005, 2015, and 2023, each causing severe damage. While every flood is distinct, the impacts have been devastating and appear to be worsening over time. The 2023 floods were the most severe in 47 years.

Many times, floods are attributed to climate change, but fundamental questions are often overlooked

In recent decades, South Asia has witnessed increasingly frequent episodes of heavy rainfall, leading to recurrent floods in several major Indian cities, including Chennai. The city experienced major floods in 2005, 2015, and 2023, each causing severe damage. While every flood is distinct, the impacts have been devastating and appear to be worsening over time. The 2023 floods were the most severe in 47 years.

Many times these floods are attributed to climate change, but fundamental questions are often overlooked:

- To what extent have human errors historically worsened flood impacts?

- Are we attributing too much to climate change while overlooking development blunders?

- How effective has the State’s conventional approach been in managing floods and droughts?

- What corrective measures have been implemented so far?

- What lessons can be drawn from past extreme events and floods?

- What strategies are needed to make cities more flood-resilient?

- How can disasters be transformed into opportunities—for instance, by securing a reliable and abundant urban water supply?

As a coastal city, Chennai must also contend with coastal flooding and sea-level rise linked to climate change. The real challenge lies in decoding Chennai’s urban and peri-urban hydrology, understanding its ecosystem in its entirety, and making meaningful, science-based interventions for both flood mitigation and drought management. The key is to design and implement climate-resilient strategies for the city-region.

The key is to design and implement climate-resilient strategies for the city-region.

Tank watersheds: Upstream and downstream

Kancheepuram, Chengalpattu, and Tiruvallur districts together once had 1,942 and 1,646 irrigation tanks, some of them very large. These man-made tanks were created by constructing earthen embankments across streams that carried monsoon floods. They were ingeniously designed so that surplus water from an upstream tank would feed into the next one downstream, creating a cascading system of water storage.

Today, however, these tanks are neglected—silted up, with broken bunds and damaged control structures. Catchment areas, floodplains, feeder channels, and even the tank water-spread areas have been encroached upon and degraded. The result is a double blow: the tanks now store very little water, while surface runoff is extremely high (over 80%). Together, this has left Chennai highly vulnerable to both floods and water scarcity.

To minimise risks, the following steps are critical:

- Study urban and peri-urban water dynamics to understand interconnected hydrological conditions.

- Map all water bodies (around 4,000) spread across the 5,904 sq km of the proposed city region covering Tiruvallur, Chengalpattu, Kancheepuram, and parts of Ranipet districts. These areas are increasingly urbanized, making protection from encroachment urgent.

- Protect catchment areas, inlet and surplus channels, foreshore zones (tank floodplains), and bunds while restoring missing links between tanks.

- Restore water bodies to their original capacity—and, where feasible, even double the capacity—so that excess monsoon water can be captured and stored, substantially reducing runoff.

- Prepare a comprehensive hydro-elevation (drainage) map covering upstream and downstream watersheds, linking Chennai and the sea.

The result is a double blow: the tanks now store very little water, while surface runoff is extremely high (over 80%).

Such a systematic approach can revive the traditional tank system, reduce flood risks, and improve water security for Chennai and its surrounding districts.

Natural flood carriers

Chennai is geographically unique, and this is truly a blessing. The city is traversed by three major rivers—something no other city in India or South Asia can claim. The Kosasthalaiyar runs through North Chennai, the Cooum through Central Chennai, and the Adyar through the South; further south, the Palar carries additional flows. Each of these rivers also feeds numerous tanks before emptying into the Bay of Bengal. Adding to this network, the Buckingham Canal cuts across all four rivers near the coast.

Unfortunately, these vital drainage systems are in poor condition due to heavy encroachments, particularly on their floodplains. Sludge and silt deposits have reduced their natural gradient and flow velocity. Though there have been several attempts to restore the rivers and the Buckingham Canal, progress has been limited. What these waterways need is sustained, year-round care and maintenance—not cosmetic “riverfront” or “canalfront” beautification projects.

Beyond the major rivers, Chennai also depends on a network of macro and micro drains such as Okkiam Maduvu, Mambalam Canal, Velachery Canal, Kodungaiyur Drain, Otteri Nallah, Virugambakkam/Arumbakkam Canal, Veerangal Odai, Captain Cotton Canal, Villivakkam Canal, and many more. These too require consistent upkeep, alongside the city’s 3,600 km of stormwater drains.

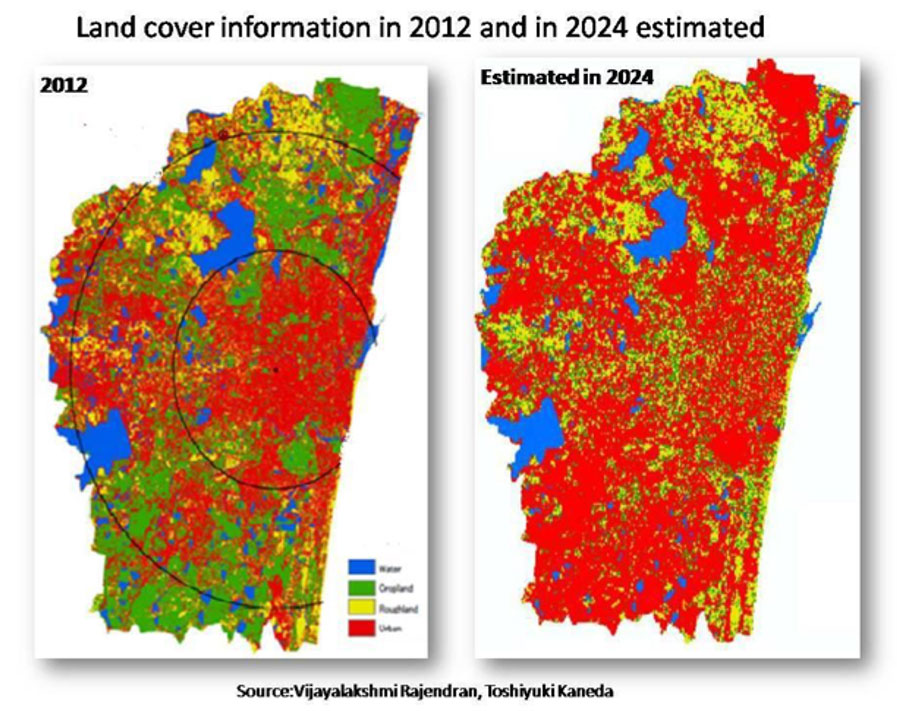

At the same time, we must acknowledge that Chennai’s urban expansion has been among the fastest in the country. Expansion is irreversible, and if left unregulated, it can be disastrous. When the city limits were extended from 174 sq km to 426 sq km, and the Chennai Metropolitan Area (CMA) to 1,189 sq km, little attention was paid to protecting ecological hotspots in the newly added zones. As a result, many lakes and ponds have been lost, while most of the Pallikaranai marshland and coastal wetlands have been encroached upon.

Little attention was paid to protecting ecological hotspots in the newly added zones.

The Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA) originally planned to expand the CMA from 1,189 to 5,904 sq km—covering the entire districts of Tiruvallur, Chengalpattu, Kancheepuram, and parts of Ranipet under the III Master Plan. But, now the CMA has decided not expand the area but perhaps intends to go for vertical development with a higher floor space index (FSI). Increasing the FSI and opting to go vertical development will have very serious consequences for stormwater drainage as well as sewage management, mainly because of increasing population density. At the very least, and at least now, the CMDA must identify and notify ecological hotspots, protecting the existing 4,000 lakes, floodplains, forests, major drains, flood buffers, and wetlands is essential. Without this, the city will once again find itself hiding behind climate change as an excuse for accumulated planning and development failures

Final thoughts

There is a lack of coordination among urban land use planners, real estate developers, municipal authorities, and key water resources departments

Chennai city, like many other urban regions, can be permanently made less risky from floods while also ensuring round-the-clock water supply even in drought years—if the measures outlined above are implemented with utmost commitment. This is the essence of turning disaster into opportunity. Yet, such possibilities stand in stark contrast to today’s dominant model of global growth, which is not merely extractive but aggressively competitive, accelerating capital concentration and reducing elected governments to mere instruments of corporate power. In its wake, land, water, and air are ravaged, biodiversity is shredded, and human suffering deepens. These models hardly address the well-being of the people and the sustainability of development. As a result, what one encounters is the increasing economic inequality, erosion of natural resources, and increasing ecological imbalances. The catastrophic urban floods we now witness are thus part of this same trajectory, rooted in the mismanagement of key natural resources such as land, water, and ecological hotspots like forests, wetlands and riverbanks. Furthermore, there is an absolute lack of coordination among urban land use planners, real estate developers, municipal authorities, and key water resources departments. These corrective measures are most critical to save the cities from floods.